Amid the chaos and destruction of World War II, the Allied powers sparked a wave of groundbreaking innovations that would not only help win the war,but also shape the future of science, technology, and modern combat. Among these innovations, there is one that may not have drastically shaped the future, yet remains a fascinating story worth exploring. So in this month’s blog article, I would like to take you back 83 years to the year 1942 in to the midst of the second world war.

The problem

To paint the picture, in December 1941 the United States of America joined the Allied forces and declared war on German-led Axis powers. Those same Axis powers, were at the height of their military success in that war. Pushing deep into the Soviet Union and stalling at Stalingrad, they had secured the Crimean Peninsula while in North Africa, Erwin Rommel was conquering Egypt.[1]

Concurrently, the naval supply line between the Allied nations, principally the Atlantic Ocean, has become a theater for German U-boats to operate in wolf packs, thereby terrorizing Allied convoys. Leading to the region being nicknamed “The black pit”. The issue at hand was the limited range of Allied aircraft at that time, which hindered their ability to provide reliable reconnaissance and protection for these convoys. The utilization of aircraft carriers was also not a viable option due to their suboptimal performance in high-seas conditions, their inadequate runways for bomber aircraft, and their inherent vulnerability to U-boats and their torpedoes. [2]

The proposed solution

In order to solve this issue, Geoffrey Nathaniel Pyke, an associate of the British Combined Operations Headquarters under Lord Mountbatten, proposed an unorthodox solution. He asserted that the deployment of conventional ice would prove to be the decisive factor in securing victory in the war. The proposal, in its simplicity, entailed the utilization of arctic ice as a means to construct floating airfields in the Atlantic Ocean. In December of that same year, Churchill formally signed a memo ordering the construction of these floating airfields made entirely of ice.[3]

The the initial plan, however, encountered a significant challenge. As icebergs typically retain 90% of their mass below the surface, leaving only 10% above the water. This meant that the icebergs would have to be of a substantial size to function as a functional airfield. The resulting proportions proved to be too unrealistic to be taken seriously, yet the concept of utilizing ice remained viable and was subsequently pursued in another project.[4]

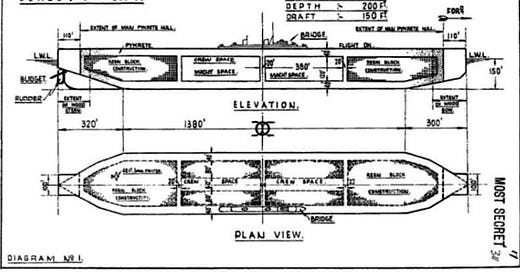

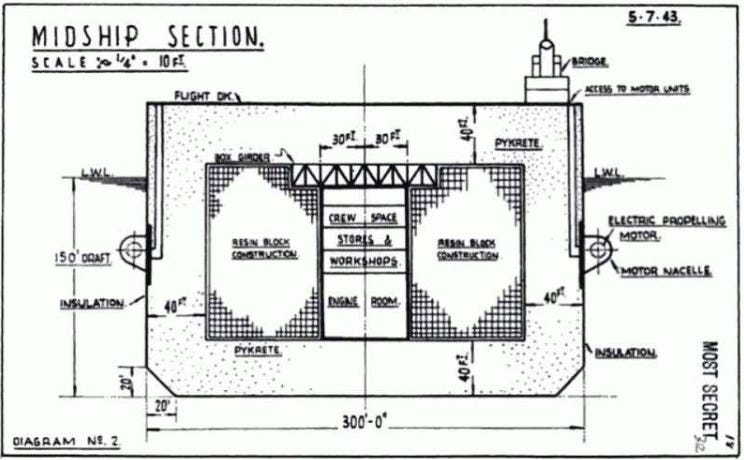

This project, designated “Operation Habbakkuk” by Pyke, involved the utilization of ice as a construction material to create a mobile ice platform capable of achieving speeds of up to seven knots. The platform was to be refrigerated by cooling pipes to prevent melting during operation. Approval for this ambitious endeavor was granted by the British Admiralty at the onset of 1943, entrusting the Canadian government with the responsibility of conducting the research, testing, and construction of a prototype "ice-carrier" on a smaller scale. In pursuit of exploring the potential of ice as a construction material, the Brooklyn Polytechnical Institute conducted research that revealed the efficacy of combining ice with wood pulp, a discovery that led to the enhancement of the material's strength and resistance to both bullets and explosions. Pykrete exhibited notable buoyancy, lightness, and resistance to melting under specific conditions. In the event of a malfunction, it could be patched with frozen water. This combination of properties rendered it particularly well-suited for the construction of Pyke's "Ice-Carrier”.[5]

The final concept entailed the construction of floating airfields from pykrete, with the intention of utilizing the interior and deck for housing personnel and materials. The exterior layer, of substantial thickness, was to be lined with pipes that functioned to cool the ice and refrigerate the entire "ship." The ship's power was to be derived from engines and generators located within. [6]

These "ice-carriers" were designed to function as aircraft carriers in the Atlantic, offering Allied aircraft the opportunity to resupply, start, or land on relatively mobile platforms. The pykrete construction of these vessels was intended to provide enhanced protection against U-boat attacks, a feature that was deemed crucial given the inherent danger of “The black pit” as it´s theatre of action.

The actual solution

While sounding incredibly interesting, in reality “Operation Habbakkuk” was ultimately terminated shortly after, between April and May 1943, due to a multitude of factors.

Primarily, the Operation required an exorbitant allocation of resources, mainly steel, which was indispensable for the construction of the ship's coolant pipes. Additionally, the procurement of wood pulp for the pykrete, a crucial component in paper production, was a significant constraint. However, the most important factors contributing to the end of Operation Habbakkuk were the technological advances made in the form of the introduction of VLR (Very Long Range) models of the B-24 Liberator, a common aircraft produced by the United States in World War II, which overcame the challenge posed by the Black Pit, allowing the aircraft to operate longer and thus providing further protection to the convoys crossing the Atlantic. Moreover, technological advances in sonar and radar made it easier to detect German submarines, while the development of the "Hedgehog" bomb made it easier to destroy them, turning them from predators into prey and drastically increasing German losses in the Atlantic. [7][8]

The increased deployment of escort aircraft carriers and the establishment of airbases in Keflavik, Iceland, and the Azores in 1943 further solved the underlying problem of The Black Pit in the Atlantic, since the area could now be more easily covered and protected by airplanes. The latter was achieved within Operation Alacrity and with Churchill calling on a treaty that was signed between England and Portugal in 1373, so neutral Portugal agreed to the building of the airfield.[9] In regard to the airbase in Keflavik, the United States Marine Corps arrived in 1941 at the behest of an agreement between the Icelandic government, the British government, and the United States government. This agreement stipulated the replacement of British troops with United States Marines, with the marines also constructing an airbase as a refueling point.[10]

In sum, these changes had a significant impact on the battle of the Atlantic, providing the Allies with the necessary options to conduct further operations and establish reliable and well-protected supply lines. This made Pyke’s solution to the now-solved problem redundant.

Future Potential?

The Arctic is increasingly a point of interest, one should think. Could we not repurpose this idea to provide an alternative solution to a problem not yet discovered?

To answer this briefly from my point of view: No. I do not think that the Habakkuk concept will ever be considered again by individuals in decision-making positions, simply because the problems it was trying to solve (limited range of airplanes, no air bases in the vicinity) are no longer present, and the absurd resource costs, either in building materials or manpower, would simply outweigh the benefits.

[1] United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. World War II Dates and Timelines.

[2] Langley, Susan B.M (1986): Operation Habbakuk: A World War II Vessel Prototype. In Scientia Canadensis: Canadian Journal of the History of Science, Technology and Medicine vol. 10, n° 2, (31). pp. 120f.

[3] Langley, Susan B.M (1986): Operation Habbakuk: A World War II Vessel Prototype. In Scientia Canadensis: Canadian Journal of the History of Science, Technology and Medicine vol. 10, n° 2, (31). p. 120.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid., 121f.

[6] Ibid., 123f.

[7] Langley, Susan B.M (1986): Operation Habbakuk: A World War II Vessel Prototype. In Scientia Canadensis: Canadian Journal of the History of Science, Technology and Medicine vol. 10, n° 2, (31). pp. 126.

[8] Government of Canada: The Battle of the Atlantic.

[9] Herz, Norman (2004): OPERATION ALACRITY. THE AZORES AND THE WAR IN THE ATLANTIC. Naval Institute Press: Maryland. pp.1 – 6.

[10] U.S. Embassy in Iceland: History of the U.S. and Iceland.

As one who was born in Canada, a snowy place (“quelques arpents de neige?” as Voltaire put it), this story reminds me of the expression, “If you have lemons, make lemonade.” Fun reading.